Do Not Make Our Grief Your Content

On the need to rethink power and space within community arts

I’m not taking this well, to put it mildly.

I didn’t wake up in a different country than the one I fell asleep in on Monday. In the hours after the election, all the social media content that circulated about how voters on the right chose misogyny, transmisogyny, transphobia, homophobia, racism, and other hatreds only made me wonder how that’s different from what we were already living. A woman more likely to don a sequin rainbow bolero than ensure gender affirming care doesn’t make that much of a difference. We were still suffering soul death, eviscerating the climate, and refusing to do anything about infrastructure, healthcare, access to save water, housing, or education at home while committing or neglecting genocides elsewhere. Despite knowing this, I spent the week struggling to overcome a new horizon of disbelief. They really do hate us exactly this much.

To be able to feel shock is the privilege of being adjacent to suffering and in solidarity with the most vulnerable, but having remained comparatively safe. My friends are grieving homelands, family members, and friends. They’re grieving people whose laughs they remember, whose minds shaped their own, whose blood runs in their veins. Unlike me, they have known that this is how much they hate us. With our differences made more explicitly clear, I am thinking now about how to proceed within our own communities.

I am once again grateful to Hala Alyan in her most recent Substack post, “on invitations,” for reminding us that the time for fully falling part, to let the grief and pain and rage sink deep and strike out, is now. I am trying to reiterate this for whomever is reading as much as I am for me. Currently, I am fighting the guilt and shame of having accomplished nearly nothing I’m responsible for since. That guilt lives cheek by jowl with the knowledge that I must reserve the right to have a human response. My humanity, I want to remember, is the most fundamentally precious thing I have left to protect before I can do or be anything else for anyone.

Folks have been asking me for my thoughts and insight, like I might have wisdom or political analysis worth something more than what the talking heads offer us. I wish I did. I nothing to offer beyond this: I know I will not survive this, or one day die proud of who I’ve been, if I fold up and comply. I need time to recover from this blow and regenerate differently. Perhaps I am excessively sensitive. Perhaps I have a responsibility to be. When I can stand all the way back up, I cannot ever again keep my head down. That I felt guilty for being insufficiently productive before I felt enraged by the obligation proves the extent to which I have complained more than I’ve fought. I don’t know yet what fighting better means to me yet. I only know it’s time to get more sensitive, not less.

Those of us who are in communities that hold each other up and thrive on one another’s care, solidarity, mutual access intimacies, and space-making have important new ethical questions to consider. I’m talking about, and to, those of us in the community cultural sphere: artists, organizers, writers, poets, podcasters, journalists, Substackers, influencers, event planners, literary and arts non-profits, venues, and folks with other ties and power in cultural programming. We have a responsibility to center Palestinian, Congolese, Sudanese, femme, trans, disabled, structurally oppressed and silenced people in our communities. White people in power, I’m looking most pointedly at you. However, as someone who is often invited to podcasts and interviews to talk about being a queer, Muslim, disabled, and poly poet, I am aware of what it feels like, to some extent, to be asked questions repeatedly that feel like paper cuts to the soul. It occurs when in veiled ways. I am asked to expose myself as human in order to count as human by sharing painful, vulnerable details about myself and my health. I do so with a smile on my face. I conclude by saying how grateful I am to be there, and how grateful to have someone make room for my story. They feel better for having me. Their audiences pat themselves on the back for having learned something about disabled people. I walk away, often, feeling like shit. Imagine what it’s like for those whose losses we cannot, in fact, begin to imagine—until they catch up to us.

And they will catch up to us. We have been as complacent as we have been because we have too much to lose, and lose we will, even amongst our wins. Meanwhile, we have a responsibility to see one another as no different from ourselves no matter what we cannot imagine, and hope we won’t have to. I’m thinking about Abu Mosab Toha’s book tour for Forest of Noise, and a deeply disturbing event I attended at Joe’s Pub featuring H. Sinno and Hala Alyan.

On Friday, October 25, the poet Abu Mosab Toha read and spoke at a sold out event at the Brooklyn Public Library on Friday, October 25. Immediately afterward, he commuted to Syracuse. Early the next morning, he spoke to Amy Goodman for the Democracy Now! news hour. Toha told stories about being abducted, blindfolded, nude, and at gunpoint, and sleeping his first night on his own Palestinian land as a brutalized detainee. On said night, he had no way of knowing whether his wife and children were alive. He told stories about all the family members, friends, and neighbors who have died, or from whom he has not heard, including a pregnant younger sister. Even Amy Goodman, who is generally more sensitive about her language than most, asked him to speak to the violence in hospitals in Gaza to “humanize” the situation there.

We cannot platform our kin as an act of solidarity only to make their grief our entertainment or virtue signal by our proximity to their struggle. We cannot keep asking people to make art that argues for the validity of their lives and that of their people, and have them talk about their losses as fodder for promotion. We cannot make it so that this is one of the few and primary ways artists are able to make money. Tokenizing is not solidarity.

Hala Alyan and H. Sinno performed as part of a podcast hosted by a well-meaning white man who writes songs in response to poems. He began by publicly shaming Hala for being late, though she appeared on stage at exactly the right time. When it came time for him to perform a song in response to her poem, he started by saying he didn’t know how to begin because “it’s so intense.” When more audience members had more questions for the researcher he had join them on stage, he referred to Hala and H. Sinno, the artists, as “pretty and useless,” ignoring the acute and obvious trauma in the bodies of the artists on stage. I walked out feeling deeply insulted for myself and for my friends. Must we make minstrelsy out of Palestinian and Lebanese pain? Is that the best we can do to show humanity? Are we sliding dangerously toward torture porn, allowing the powerful to pat themselves on the back for making space for the oppressed without strategizing to make those appearances the most impactful as possible?

As I work out how to face each day, I am thinking about how to ensure that we consolidate power amongst ourselves so we can protect ourselves from the showcasing of our pain, and create space for our voices in safe, supportive spaces where we think in “we” rather than “us” and “them.” There is no liberation for one without liberation for all. It’s time we give up institutional routes to space and power and learn definitively that the micro, the local, the community-based is where we must begin, with eyes wide open, and for God’s sake, some humility.

Poems that hit hard this week:

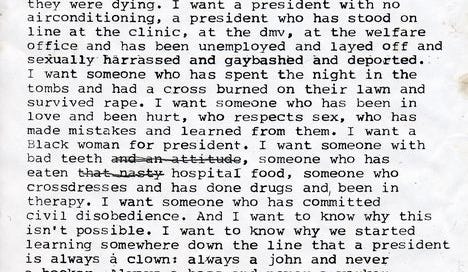

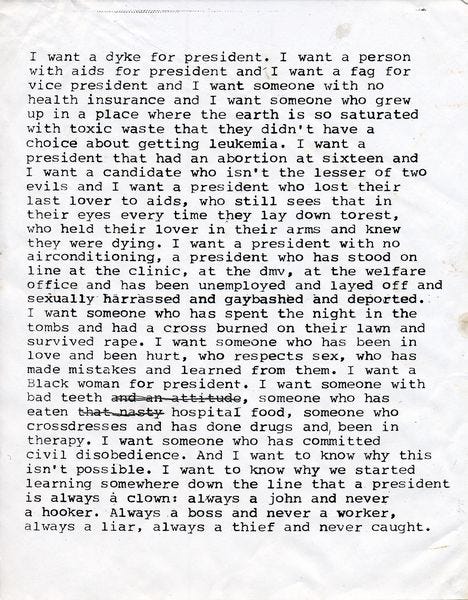

“I want a president” by Zoe Leonard

“Silhouette” by Ladan Osman

”I Am The Daughter My Mother Raised to Confront Them” by Margo Tamez

Until next time.