The Sitayana, and On Writing into Silence

Considering of South Asian Diasporic Arts and Cultural Criticism

As of August 15, I’ve been in New York City for eighteen years, exactly the number of years I lived in Italy before I moved. When I hit ten years—which some believe is the mark of becoming a “real” New Yorker, whatever that means—I threw a party with besties to celebrate. Despite the political storms on the horizon, 2015 still felt like a time of promise and possibility. With few folks in my community feeling secure across various crises, I find myself far less sanguine today.

Desc: In the only photo I can find from my freshman year of college, I’m lying diagonally on a fuzzy red rug wearing a blank tank and blue jeans. The photo is taken from above my head.

I landed here a callow youth with little more than hope, trauma, and highly inaccurate ideas about America. Since, I’ve learned the profoundly unique nature of everyone’s lived experience, and that my experience, too, matters. Despite a tripartite cultural identity (Bangladeshi, Italian, American citizen) that makes me a foreigner everywhere, and gender/sexual identities that alienate me from traditional forms of cultural and familial acceptance, I have been able to carve a place for myself here by being sincere and embracing one our last actually inalienable rights—that of being authentically peculiar.

One of the developments I’ve tracked over the last several years is the growth of a vibrant, varied, and dynamic South Asian diasporic community of artists, writers, poets, dancers, choreographers, filmmakers, and dramaturges of a kind I’d never dreamed of. Growing up, there were so few of us in mainstream media, and those involved in independent arts were often struggling against the pressure to do have “respectable” middle-class careers and embody model minority myths regardless of the odds. The pressure remains, but we’re increasingly bucking against it, emboldened by the rapid growth of mainstream figures in pop culture (think Hasan Minhaj, Mindy Kaling, Hari Kondabolu, Aparna Nacherla, Aziz Ansari, Lily Singh, Padma Lakshmi, Kal Penn, Dev Patel, Maitreyi Ramakrishnan, Poorna Jagannathan, Megan Suri, Ritu Arya, and more).

The majority of the mainstream is Indocentric and does not yet represent the massive diversity, difference, and tension of the subcontinent. Still, I believe it’s fair to say that we are finally learning that to understand ourselves and each other, we have to write our own stories. We need tell our stories, and our see our experiences represented elsewhere. We also need as many stories not like our own within the community so that we can learn from one another and expand our own horizons, together with those of the dominant culture. This effort is particularly under threat due to the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers’ refusal to meet the demands of the Writers Guild of America and SAG-AFTRA, but we persist. A show I saw last night highlighted the importance and impact of this struggle, as did the energizing opportunity to speak informally with its creators afterward about the questions that face those of us in the arts today.

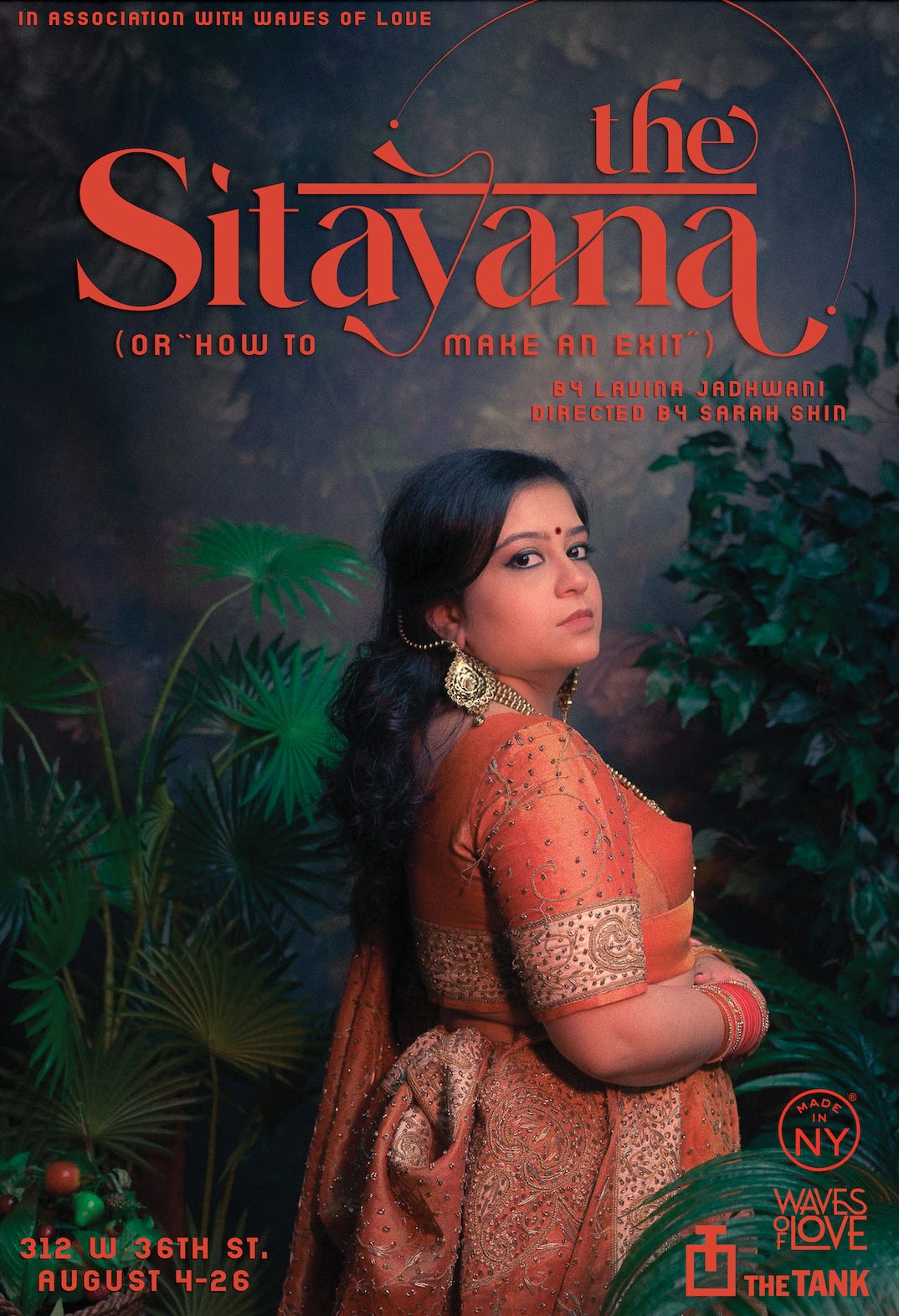

The Sitayana (Or “How To Make An Exit”)

Written by Lavina Jadhwani, directed by Sarah Shin, and performed gorgeously by Kendra Jain, The Sitayana is a one-woman show that adapts the Hindu epic The Ramayana and tells it from the perspective of Sita, the tale’s sole female protagonist. Sita is a goddess created from the Earth as a daughter for King Janaka. In The Ramayana, she marries Rama, Vishnu's avatar and the epic's hero, and becomes a national and religious symbol of ideal womanhood: self-sacrificial, pure, loyal, and devoted to her husband as her god. In the original, Sita has a supporting role. She is precious, delicate, and pure, and her strength is evidenced her loyalty to Rama as she resists her captor Ravana’s sexual advances when she is kidnapped. (There are many questions one can ask that undoes this logic, but the epic does not conceive of ideas of rape and consent in the way we might today. For whatever reason, Ravana’s insistence on bedding her is framed as a temptation rather than prolonged torture.)

Rarely do we see Sita’s story as one that exposes how patriarchal Hindu culture can find fault with even the most unimpeachable of women. Sita must prove her loyalty in a literal trial by fire, only to find Rama’s trust shaken again by simple rumors. The Sitayana gives overdue voice to Sita’s silence, and in the process, exposes the structures that silence her. Jain plays Sita across multiple stages of her life, from her early teens through her old age. Over 90 minutes, I felt as if I’d genuinely watched the journey of every chapter of a woman’s life from innocence, to maturity, to commitment, to self-understanding, and ultimately, self-affirmation in the form of a simultaneous defeat and victory, i.e. her glorious “exit” back to Earth from whence she came. Jain also plays every other character—most of whom are men—in the epic. They are subject to her characterizations alone, disallowing them to take up the space they are granted in the original. Jain has us entirely in her thrall as she plays them. She does extraordinary full-body transformations into each of the men instrumental to her story—her father King Janaka, her husband Rama, his brother Lakshman, the monkey-god Hanuman, and her captor, Ravana—embodying their voices and body language (movement direction by the talented Ishita Milli of IMGE Dance) in a manifestation of authoritative masculinity that combines Jewish-American, Italian-American, and “bro” culture, to hilarious and strangely convincing effect.

This play on the audience’s range of cultural familiarities extends through the show’s entire conception. Jadhwani and Shin have Sita speaking directly to the audience, assuming their knowledge of American pop culture, ancient Hindu mythology, and certain words in Hindi, evoking hilarity and sorrow that much more effectively for how much Sita speaks our language. Her monologues, interior and exterior, acknowledge Sita’s sexuality, loneliness, physical exhaustion, and sense of practicality. The music in the show is by diasporic desi musicians who blend hip-hop, pop, and classical Indian genres, not unlike the verbal and gestural languages of the show, also as a reflection of who the play is by, and who it is for. It refuses to explain itself beyond absolute necessity, marking an important stance: this is not a show that imagines a white viewer to whom it must explain the need and importance of its existence. It takes a wide step over that anxiety and takes up space in significantly more beautiful, interesting, and thought-provoking ways. My desi diasporic kin, go see it. Everyone else, go see it. Do a little Wiki if you’re unfamiliar. You won’t be disappointed.

The Sitayana is playing at 7PM on August 18th, 20th, 22nd, 25th, and 26th at The Tank, 312 W 36th St, New York, NY. Tickets here.

*For an accessible novelized version of The Ramayana, consider Ramesh Menon’s modern retelling.

On The Future of Pain Baby:

Last month, I decided I would write write micro-reviews of collections of poetry read as part of The Sealey Challenge, a social practice of reading a collection a day for the entire month of August. As a chronic illness warrior with pain and fatigue syndromes, I am, predictably, moving slower through my stack than I had hoped. However, my pace has rendered me conscious of the value of slow time with poetry, how gobbling such nourishment quickly and in great quantity can diminish one’s appreciation for its riches. I will curate a select few books that have not only deeply moved me but have informed my thinking about my own collection in due course.

Seeing The Sitayana and connecting with folks during its afterparty reinvigorated my understanding of the importance of writing about desi diasporic arts, for my own sake. I had never lost interest, but sitting alone in my home, I occasionally become deflated, thinking: Aren’t we all talking about this to death? Aren’t these questions and debates old, now? Does anyone care about my particular perspective?

Considering my own enthusiasm and the excitement I’ve witnessed for the increasing number of showcases and festivals that announce our existence and illuminate our stories, I am clearly doing myself no favors with this line of questioning. For the rest of the year, I’ll be turning more of my attention to South Asian diasporic arts and cultural criticism to explore these and better questions: Where else are the silences that need writing into, and what silences are we complicit in sustaining? How do we toe the line between telling frank and complex stories and resisting the ones that paint us and our families in a negative light? What violences do we continue to carry out upon one another while dependent on one another’s solidarity to survive in the Euro-American landscape? What happens when our stories are also queer stories, stories of illness and disability, or love between characters with opposing political and religious backgrounds, or of poverty and struggle? (South Asian diasporic communities are notoriously difficult to engage on matters of illness and disability. Disability is often cloaked with stigma along the lines of gender, class, caste, and respectability. This, too, is a silence that quite literally kills, and begs to be undone.) What are we doing with the representation and rehabilitation of South Asian masculinity? How do we honor our debt to African American politics, arts, and literature? How do we stick together on these shores while our people tear each other apart on the subcontinent? How do we show up for each other in earnest solidarity while honoring our roots? How do we contend with toxic Hindu nationalism, doctrinaire Islam, the tensions in between, and where it leaves our Buddhist, Christian, Zoroastrian, and secular kin? When are we framing West Indian and Caribbean stories as part of our wider history and contemporary cultural landscape, when are we not, and why? Who is getting a chance to tell their own stories, and who are we leaving behind? What stories aren’t yet being told, and what barriers keep them fettered?

News and Announcements:

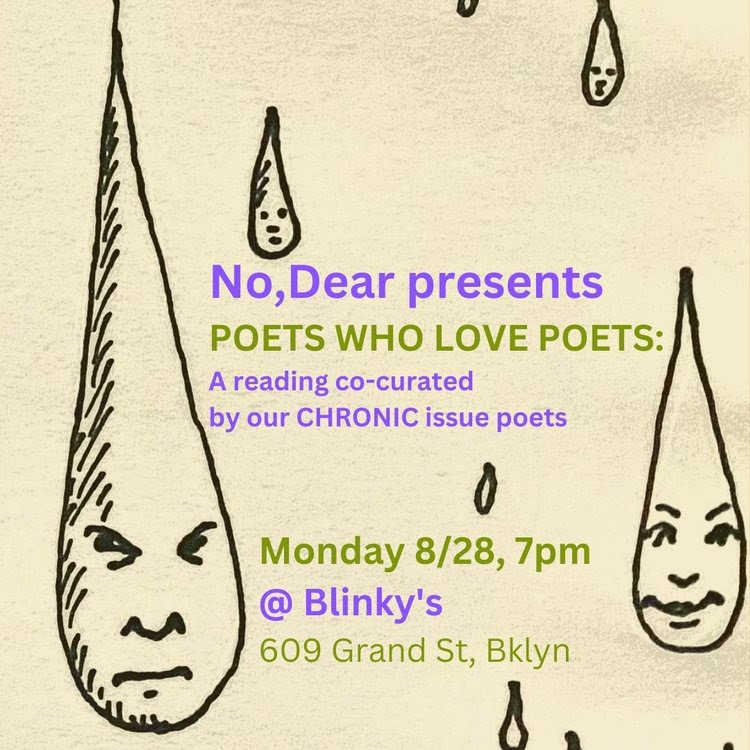

Upcoming Reading: No, Dear Magazine’s Poets Who Love Poets

No, Dear Magazine, a wonderful juggernaut of a poetry magazine publishing New York City poets for which I served a guest editor earlier this year has a beautiful tradition of inviting poets featured in their pages to nominate poets they love to read with them at a reading called Poets Who Love Poets. The poets published under the theme CHRONIC invited their beloved poets to read with them on August 28 at Blinky’s Bar, 609 Grand St, Brooklyn, 11211 at 7:00 pm. Please join us!

Podcast Appearance: Sex Education in the City

I was recently on Sex Education in the City with the inimitable health and sex educator, dear friend, and former colleague Drew Miller and his excellent colleague Dr. Rachael Gibson to chat about teaching today’s brilliant youth, modifying classes with disability justice in mind, understanding gender across culture, why grown cis-men should know how to feed themselves, and a whole lot more fun stuff! I strongly recommend this podcast to all radical educators interested in empowering and uplifting young people. I spend an odd amount of time referring to everything in my life as Whack-a-Mole, and I can’t stop thinking about how accurate that feels… Check it out!

Internship at Brooklyn Poets: I am deeply excited to share that starting later this month, I am one of the interns at Brooklyn Poets! This organization and space houses workshops, craft labs, readings, and other events to cultivate relationships and nurture the work of Brooklyn poets. The space is open during the day for poets to enjoy some sunshine through enormous windows, cafe-style seating, free coffee, and books for purchase! If you happen to be a fan of the space, are taking a workshop, or are curious about what Brooklyn Poets does, drop by on a Thursday or Friday evening after August 24 and chat with me!

Some more magic to check out:

Chapbook Drop: Amatan Noor’s Not Guilty

Seeing badass Bangladeshi-American women speaking their truth into the world fills me with such excitement and pride. My friend, the beautiful poet Amatan Noor, has her stunning chapbook, Not Guilty, available for pre-order, and I strongly urge you to go in on it and allow yourself to be swaddled in this brown girl anthem of love and survival. You better believe I’m going to be writing about it as soon as its launch is public.

Music for Survival/ Futurity: Shamik’s Hope and Mirrors

My friend the Chicago-based Indian-Canadian electronic musician and producer Shamik’s 2023 EP, Hope and Mirrors, has been on loop on my train rides and as I knock out the tasks of living in a period of profound rage and malaise. Shamik combines soothing layers of contemporary and archival samples of Indian music and elements from many other genres to maneuver of the element of surprise, propelling the listener forward in space while taking all of time along with them. His work defamiliarizes by juxtaposition to prompt excellent questions about what belongs to whom and where our emotional associations come from, all while inspiring bedroom solo-dancing with stank-face. The track “We Are All Gems” really fucks me up in the best way. Strong recommend.

Spiderverse Love Continues: Micheal Weston’s Spidersona Swing

Watching my boo Michael Weston work has been teaching me a great deal about illustration, storyboarding, animatics, and animation, and I am continually impressed by his creations. Despite allegations of labor abuse on the movie, The Spiderverse’s malleability has became a real beacon for animators. Inspired by the trend, Michael made this cool Spidersona video using Blender, and I find it too awesome not to share. Enjoy!

Until next time, lovelies.